The role of the Armed Forces in the Colombian peace process

Photo by FAOALC

Photo by FAOALC

Colombia’s recent history has been marked by internal armed conflict and efforts to end it. For nearly six decades of war the response of the Colombian state to the insurgent threat has primarily been one of military confrontation. But at the same time all of the country’s governments have also initiated political negotiation processes. Some of these initiatives have led to the demobilisation of several armed groups. In these scenarios, the Armed Forces have played an important role in the war, and a smaller one in the peace negotiations.

This situation changed significantly with the recent negotiations with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia/FARC). For the first time the Armed Forces (the military and police) played a key role in both the negotiations and the implementation of the peace agreement. This active involvement on the part of the state security forces has been an essential part of and key contributing factor to the most successful peace process in Colombia of the last six decades.

The purpose of this report is to describe and analyse the contribution of the Colombian Armed Forces to the theory and practice of building peace. 1 In doing so, the analysis will focus on:

- the changing military response to the insurgency and the issues that brought about these changes;

- the specific role of the military in the peace negotiations, and the infrastructure they created to carry out this role;

- the gender-related innovations in aspects of the ceasefire and the laying down of arms; and

- the challenges created by the unprecedented leading role played by the Armed Forces in the Colombian peace process.

The pendulum between war and peace

Several armed guerrilla groups 2 emerged in Colombia in the 1960s and 1970s in response to what they described as the left-wing movement’s lack of opportunities to participate in the country’s political processes. Against the backdrop of the Cold War, the Colombian military – supported by the United States – concentrated their efforts on fighting “the expansion of communism on the back of the successful Cuban revolution”. 3

Initial attempts at a negotiated solution to the armed conflict in Colombia took place in the 1980s under the presidency of Belisario Betancur. Since then, all of the country’s governments have combined their military response to the insurgency with attempts at dialogue.

In the early 1990s, influenced by the paradigm shift symbolised by the fall of the Berlin Wall, peace negotiations culminated in peace agreements with several revolutionary groups. A decade later the government also reached a demobilisation agreement with the right-wing paramilitary groups.

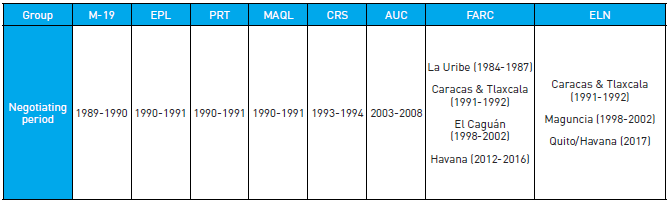

Table 1: Colombian government negotiations with guerrilla and paramilitary groups*

* The full versions of the abbreviations used in this table are given in footnote 2.

Towards the end of the 1990s the two guerrilla groups that had not demobilised increased their various anti-government activities and, through a series of assaults on police and military barracks, for the first time convinced a wide range of social and political groupings that the guerrilla movement was capable of taking power by force.

President Andrés Pastrana’s government (1998-2002) was notable for two apparently conflicting approaches to the conflict. On the one hand, he won the elections promising peace. In a move that was highly criticised by the military, he agreed to remove the Armed Forces from an area of territory the size of Switzerland as a gesture of goodwill prior to holding negotiations with the FARC. Soon after this goodwill gesture, however, he pushed through the Colombia Plan, which was initially designed as a strategy to curb illegal drug production, but which ended up as a renewed counter-insurgency offensive, with strong U.S. backing. Simultaneously, right-wing paramilitary groups grew as they had never done before.

There was a second escalation of the military response to the insurgency when the peace negotiations with the FARC broke down in 2002. Against a backdrop of the so-called global war on terror, President Álvaro Uribe (2002-2010) developed his policy of “democratic security”, which denied the guerrilla movement any form of political legitimacy and committed the Armed Forces to fighting the FARC with unprecedented intensity. During this period government troop numbers expanded to over 400,000, and Uribe’s approach did in fact succeed in pushing the guerrillas back to the unpopulated edges of the country and neutralising well-known guerrilla leaders. Even so, under the Uribe presidency there was also contact with the FARC in an attempt to establish a new negotiation process; peace negotiations with the Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN) guerrilla movement took place in Cuba; and a demobilisation agreement was signed with the paramilitary Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC).

In this swinging of the pendulum between war and peace, the moves towards political negotiations and military action were completely unconnected processes. The military were responsible for ensuring security and implementing disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR) with the groups that signed peace deals. But they were not involved in the direct negotiations, and on several occasions this triggered a perception among the military that they were being left on the sidelines.

Writers such as Alfredo Rangel and Lozano Medina claim that “the actions or omissions of the military determine to a large extent what happens in these peace processes” (Rangel & Medina, 2008: 265), while Carlos Velásquez argues that the attitude of certain governments towards the Armed Forces demonstrates “ignorance of the contribution that they could make to the peace policy, designing a coherent military strategy that is focused on achieving political objectives” (Velásquez, 2011: 57).

In 2010 the Armed Forces decided to conduct a robust analysis of potential peace opportunities and began to examine the reasons for the failures or successes of the efforts already made to reach peace agreements with the various armed groups operating outside the law. This process contributed to the drawing up of a proposal for a possible peace process scenario.

Key factors in negotiations with the FARC

Other NOREF reports (Herbolzheimer, 2016; Nylander et al., 2018) describe the factors influencing the commitment made by the government of President Juan Manuel Santos and the FARC to implement peace negotiations. In the present report we wish to emphasise the developments that influenced the Armed Forces’ analysis and led to the military becoming involved in the peace negotiations.

Adaptability of the guerrillas

Between 2006 and 2008 the FARC suffered major strategic setbacks, including the neutralisation of top-ranking leaders, the reduction of its areas of influence and the progressive weakening of its structures. From 2009 onwards the FARC reacted to this military offensive by carrying out its “Rebirth Plan”, which led to an increased use of improvised explosive devices and snipers, and significantly fewer losses among its fighters.

The guerrillas’ resilience was particularly significant, given that the Armed Forces were at peak strength thanks to military investment and spending during the administrations of presidents Pastrana and Uribe, which had enabled an unprecedented development of military technology, joint operations between the military and the police, the restructuring of the intelligence service, and increased special operations capability.

The need to explore new ways of ending the conflict

The military offensives that took place in several parts of the world after the attacks in the United States on September 11th 2011 did not achieve the desired results. Several analyses were published that were critical of purely military counter-insurgency strategies 4 and advocated the need for political negotiations and economic and social reforms, as well as for increasing the legitimacy of military forces.

Colombian military analysts studied these reports, and they were made available to senior officers in the intelligence services, planning and operations. This provided food for careful thought that, together with evidence that the decline in the guerrillas’ capabilities had stabilised, indicated that it was the right moment to explore alternatives for a negotiated end to the Colombian conflict.

The Strategic Leap

In 2009 the then-deputy minister for international policies and affairs at the Defence Ministry, Sergio Jaramillo, 5 decided to establish a structure for developing the thinking behind military decisions.

The Strategic Leap started as a coordinating tool to implement the Territorial Consolidation Plan, with which the Uribe government attempted to achieve the united, multilevel front required to defeat the insurgency. The plan emphasised social development initiatives rather than military action in areas where the guerrilla, paramilitary and criminal groups were present.

The Strategic Leap was also the first joint exercise in reflection involving the military, government departments and academics, and marked the first occasion that the Colombian military had analysed the effectiveness of the armed confrontation with the insurgency. This would prove to be the genesis of the Strategic Review and Innovation Committees (Comités de Revisión Estratégica e Innovación), which are still currently the main tool used for military planning.

Signals from the FARC

At the same time the guerrillas started to send signals suggesting the viability of starting a new peace process: in multiple communiqués between 2011 and 2012 the FARC expressed its wish for a political solution to the conflict that could be reached through dialogue. At the same time the ELN made repeated references to its “readiness to seek a political solution to the conflict”. As a confidence-building measure, in February 2012 the FARC announced that it would stop kidnapping people – a practice that represented a violation of international humanitarian law.

Military preparations and infrastructure during negotiations

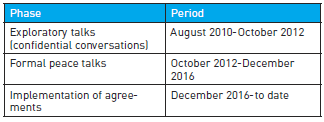

The peace process with the FARC was divided into three phases:

When the government decided to begin negotiating with the FARC, the Defence Ministry considered it necessary to develop a strategy that would enable the Armed Forces to contribute to smoothing the path towards the signing of a peace agreement and implementing it according to three strategies:

- Consolidating the Victory focused on military action against illegal armed groups, including the FARC, to reduce the elements of violence and maintain military pressure on the guerrillas so that they would continue to negotiate.

- Transition was designed to guide and articulate the Armed Forces’ approach to ending the conflict. This included designing procedural guarantees for members of the Armed Forces accused of crimes relating to the conflict; work on historical memory; participation in the forthcoming Truth Commission; and drawing up alternative approaches to a ceasefire, the disarmament of FARC members and their reintegration into civilian life.

- Transformation focused on modernising and reorganising the Armed Forces and developing their capacity to operate effectively in a future post-conflict scenario.

One of the main new features of the negotiating agenda was the FARC’s preparedness to discuss laying down its arms and its willingness to relinquish its demand to include the issue of security sector reform in the peace negotiations. These factors were a key reason why the security forces trusted the guerrilla movement’s commitment to stay with the process until its successful conclusion.

Another unprecedented move was the inclusion in the government negotiating team of two generals from the active reserve, one from the Army (Jorge Enrique Mora Rangel) and another from the National Police (Oscar Naranjo).

The government created teams comprising military and police staff and civilians to design and implement the institutional strategy needed to negotiate and implement the peace agreements, above all in relation to Article 3 of the peace agenda: a bilateral and definitive ceasefire and cessation of hostilities, the laying down of arms by the FARC, and the reincorporation of its members into civilian life.

One of the teams was part of the Issues Division of the Office of the High Commissioner for Peace (Oficina del Alto Comisionado para la Paz), while another reported to the Defence Ministry and was called the Defence Sector’s Advisory Roundtable for Peace Talks (Mesa Asesora del Sector Defensa para las Conversaciones de Paz).

These teams analysed a range of different scenarios using predictive methodologies and “Red Team” exercises, which is a process that encourages participants to put themselves in the shoes of their counterparts in order to understand their points of view and probable intentions. The work on scenarios was supported by selecting staff from the Armed Forces and National Police who were trained in DDR, negotiation and ceasefire processes. This training was very useful for reinforcing the back-up teams for the negotiations.

One of the most complex tasks was to define the defence sector’s negotiating red lines; these were submitted to top leadership in the government for approval and included the following: the guerrillas should be disarmed and violent activities on their part should cease; the ceasefire and disarmament process should be verified and monitored by neutral observers who would focus on the effectiveness of the process; and in the demobilisation phase no part of the country would be out of bounds to state institutions.

At this stage we should highlight the work conducted at the outset of negotiations to analyse the lessons learned from other processes around the world about the role of the military in post-conflict scenarios. The research took the form of an internal working paper drawn up by officers in the research teams, which came up with interesting results, such as the following:

- Military participation during the negotiation tends to be of a mentoring or advisory nature, without greater involvement in making decisions.

- When military personnel are designated to take part in peace negotiations, they generally receive little support from their commanding officers.

- The pedagogy that is supposed to inform and create support for peace negotiations among military personnel tends to be patchy and incomplete.

- The lack of continuity of tenure among senior officers vvb – whether because they are replaced or because of disagreements with the government – has an impact on the military’s support for the process.

- Most peace negotiation processes include security sector reforms, to a large degree because of the military’s lack of legitimacy and their portrayal as losers in the peace negotiations.

- In the implementation phase of a peace agreement, disarmament and demobilisation are easier to implement than the reinsertion of combatants into society and the rollout of the social and economic reforms designed to benefit the population as a whole.

- A ceasefire prior to negotiations or as a precondition for starting a negotiation process has been used in various cases as a strategy on the part of some illegal armed groups to rearm, buy time, or reduce pressure at the negotiating table and drag out talks without making any progress.

Working with the FARC in Havana

The Havana peace negotiations took place without a ceasefire. Even though the FARC insisted on a break in hostilities to create an atmosphere conducive to the holding of dialogue, the government considered that discussing the means and verification of a ceasefire before agreeing to significant points on the political agenda would be a distraction. The FARC then decided to implement unilateral ceasefires, which undoubtedly helped to increase trust on the part of the government and sectors of public opinion regarding the guerrillas’ commitment to negotiations.

Discussions in Havana about the sub-sections of the ceasefire agreement dealing with the bilateral and definitive cessation of hostilities and the laying down of arms did not begin until March 2015, when agreements had already been reached about rural reform, illegal crops and political participation. To this end the government and the FARC agreed to set up a Technical Subcommittee for Ending the Conflict (Subcomisión Técnica para el Fin del Conflicto/STFC) consisting of 15 men and women from the FARC (including members of its Secretariat) and 15 from the government (including senior officers such as generals and admirals, as well as officers who were experts on security and DDR). The STFC met over a period of 20 months until the parties managed to reach an agreement on this issue.

One of the first steps agreed by the parties was to listen to experts on and participants in other DDR processes around the world, such as those in El Salvador, Guatemala, Nepal, Sudan and Zimbabwe. 6 The aim was to learn about different perspectives that could be used as input for the debate at the Havana negotiating table.

All the proposals put forward by the military team had been studied beforehand by the support teams in Colombia and required prior approval from the civilian, military and police leadership, which included the Defence Ministry; the commander of the Armed Forces; the director of the National Police; the head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff; and the Army, Navy and Air Force commanders.

The talks were governed by the principle that “nothing is agreed until everything is agreed”. This enabled technical drafting commissions to be set up – with four or five members from each delegation – to work through the specific details of the partial agreements.

Two main stumbling blocks delayed the moment when an agreement could finally be reached. The first was that of defining the future location of the FARC’s structures after the peace deal was signed. Initially, the FARC wanted concentration areas to be created for each of its structures, but it was finally agreed that there would be 26 demilitarised zones (zonas veredales and puntos transitorios de normalización) that would be the sites of the FARC’s structures for laying down their weapons and making the transition to legality, and where the process of rejoining civilian life would begin.

The other contentious issue was that of the laying down of arms, since the FARC wanted at all costs to avoid a handover of its weapons to the Armed Forces, which would have been interpreted as a defeat and humiliation. The ideas put forward by the United Nations (UN) experts to resolve this issue provided the atmosphere of calm and trust needed for both sides to be able to support the model agreed on for monitoring and verifying the laying down of arms.

The dynamics between the military and the guerrillas

The arrival of the military in Havana was seen by some of the guerrilla fighters as a definitive step that demonstrated the government’s desire to move forward with the negotiations. The deceased leader of the FARC, Manuel Marulanda Vélez (alias “Tirofijo”), had said publicly on many occasions that when Colombia’s military were involved in negotiations, the confrontation between the government and the FARC would be ended.

Because the FARC was classified as a terrorist group, at the start of the negotiation process each of the military delegates had to be provided with a document signed by the president authorising them to establish contact with the guerrillas. This document empowered them to participate in the negotiations solely and exclusively with regard to the matters defined in the STFC’s mandate.

From the outset, con tact between the military and the guerrillas took place in an atmosphere of mutual respect. The government delegation acknowledged the authority of the FARC’s internal command structure. The members of the Colombian military in the government delegation, most of whom were trained intelligence personnel, recognised that if an agreement was to be reached with the FARC delegates, the process could not be one of one side imposing its demands on the other, but of building a peace agreement together in an atmosphere of mutual respect. This recognition by each side of the other as legitimate opponents and negotiating partners contributed to overcoming subsequent negotiating difficulties.

As requested by the government delegation and accepted by joint approval, it was decided that contact would only occur at the negotiating table and not elsewhere, except in a small cafeteria next to the room where the talks were being held, where delegates could take a break from the tough dynamics of the negotiations.

The military emphasised that their contributions to the STFC were basically technical, differentiating them from the political deliberations occurring at the main table. This fostered a “can-do”, pragmatic working climate.

Other factors that helped the military and guerrillas work together was their knowledge of the terrain and both parties’ experience of their contacts with the population affected by the conflict. Both sides’ experiences on the ground were shared and listened to carefully by the delegates, adding an element of shared responsibility that should ideally be retained as part of the new national reality.

But the construction of the model for the ceasefire and the laying down of arms was far from easy. During the negotiations several incidents occurred in Colombia that created additional tensions and even temporarily put the negotiations on hold. The adverse effects of these incidents were overcome because of the shared determination to put an end to the armed confrontation.

Creation and rollout of the Monitoring and Verification Mechanism

After analysing domestic and foreign good practices, the STFC decided to create seven subject-specific teams. 7 The team in charge of inputs for the design of a Monitoring and Verification Mechanism (M&VM) for the ceasefire and laying down of arms agreed on the shared criteria for creating an efficient and flexible mechanism that would help to generate openness, credibility and confidence in the M&VM process.

This was how an original and innovative three-party mechanism, comprising staff from the Armed Forces, the FARC and the UN (military and civilian personnel), all of whom were unarmed, came into being. This mechanism also featured the effective inclusion of women from all three bodies at all levels of the mechanism. This threeparty monitoring mechanism provided all parties and Colombian society at large with a dual guarantee: impartial observation by the international component and direct observation by the government and the FARC on the ground, in compliance with their mutual commitments.

The M&VM had three levels: a nationwide level, a regional level with nine regional teams, and 26 local monitoring structures deployed in the areas to be defined as locations where FARC structures would assemble and lay down their arms.

The M&VM comprised 323 members of the FARC, 440 personnel from the Armed Forces (287 military and 153 police), and 538 international representatives, making a total of 1,301 personnel. The international observers came from 19 countries, but mainly from Latin America (M&VM, 2017).

The need to interact with civil society was a factor when designing the M&VM, the aim being to institute a permanent process of information exchange with Colombia’s citizens and civil society organisations (CSOs). The fact that CSOs could create their own verification mechanism, one that provided information and supported the work of the institutional mechanism, represented an international innovation (Lledín & Carrillo, 2017). A public information strategy and a close relationship with the civil population meant that there was a high level of buy-in and support for the verification mission.

To roll out the monitoring mechanism, the Armed Forces created a Joint Monitoring and Verification Command that reported to the pre-existing Strategic Transition Command, while the National Police created the Peacebuilding Police Unit.

Setting up these three-party teams involved training the military, police, guerrilla, and UN personnel in the protocols and other contents of the agreement on a Bilateral and Definitive Ceasefire and Cessation of Hostilities and Laying down of Arms. A method for training the trainers was initially designed: a group of 25 military, 25 guerrillas and 30 members of the UN Mission in Colombia received initial training that enabled them, in turn, to prepare the 1,301 members of the M&VM.

These joint training sessions were the first opportunity for people who in the past had confronted one another on the battlefield to meet personally and build up the necessary trust to work towards a new, shared goal. Developing the contents of the support materials was a joint effort of the three groups (military and police, guerrillas, and UN staff).

The three-party mechanism was a success. Observing the ceasefire jointly meant that the disagreements that inevitably arose in the monitoring process could be overcome swiftly and was a factor in generating trust between the members of the Armed Forces and the FARC.

In just 22 days the FARC moved 6,934 of its members to the 26 demilitarised zones, and on September 22nd 2017 the M&VM certified the completion of this process. The FARC honoured its commitment to lay down its arms, which were handed over to the UN Mission in Colombia for destruction, after having been transported, registered and stored.

During the 12 months of the M&VM’s existence the parties scrupulously respected the ceasefire. According to the M&VM’s closing report (UNMC, 2017: 11), approximately ten members of the FARC were murdered, but most of these murders were attributed to criminal gangs and FARC dissidents. The M&VM reported a total of 160 incidents, all of which were swiftly handled. The laying down of arms was completed within the scheduled time span and without major difficulties.

When the M&VM’s tasks were concluded in September 2017, this mechanism had overcome major challenges in terms of security, operations, logistics, and human and administrative resources.

The inclusion of women in the negotiation and verification of the ceasefire and laying down of arms

Over the course of the last 20 years a great deal has been learned internationally about how war impacts men and women differently, and about the importance of gender policies to respond to the needs and guarantee the rights of social sectors that are often marginalised when decisions are taken. This knowledge has translated into many UN Security Council resolutions and many other legally binding agreements worldwide, but has been poorly reflected in practice.

The Colombian peace process created another precedent for an innovative approach to women’s participation in peace negotiations – including security issues (CIASE & Corporación Humanas, 2017). Some delegations were composed of nearly 50% women, which gave the Havana talks a distinctive character. Both parties also agreed to create a Gender Subcommittee, with the main purpose of guaranteeing the inclusion of a gender perspective in the drafting of the peace agreements. These developments were the outcome of pressure from civil society and the collective efforts of women of all political affiliations in both Colombia and Havana. They were also a response to the reality of a guerrilla force of which 32% were women.

The gender approach was included in the Bilateral and Definitive Ceasefire and Cessation of Hostilities and Laying down of Arms agreement, because both parties wanted it, but this was mainly because of the presence of women on both subcommittees. Despite being in the minority in this space, they became the key factor in achieving the effective inclusion of a gendered approach. The coordination between the work of the Gender Subcommittee and the women on the STFC (several served on both committees) was pivotal in achieving this. The gender approach encapsulated four main tenets: (1) affirmative measures and inclusive language would be included throughout the text of the agreement and its protocols; (2) training in applying a gender perspective would be given to the staff involved in rolling out the agreement; (3) the logistical process for implementing the agreement should take into account the differing needs of the people who were going to form part of the ceasefire and laying down of arms processes; and (4) women would participate in all the procedures involved in implementing the agreement. The parties also agreed that gender-based violence should be classified as a violation of the ceasefire agreement, which imposed on those involved an element of zero tolerance for violence of this kind.

In total, 19% of the people involved in the M&VM were women: 53 were military/police and 56 were UN civilians, while 85 Colombian women (including members of both the Armed Forces and the FARC) were stationed at all the M&VM locations, particularly the regional and local sites, where they carried out functions of all kinds and took on significant responsibility.

To strengthen the training, gender-based violence prevention and gender-based tracking initiatives, the M&VM created gender focus groups (made up of one person each from the government, the FARC and the UN) at the national, regional and local levels, and implemented a Gender Plan.

Together with the High Commission for Human Rights, the Office of the Counsellor for Women’s Equality and the Ministry for Social Protection, the M&VM designed guidelines for appropriate responses in situations of violence against women or people from the LGBTI community in the demilitarised zones and areas close to these zones.

These efforts largely succeeded in preventing sexual violence – which was disgracefully all too common in other peace missions – since, during the period of the bilateral ceasefire and the laying down of arms by FARC combatants, very few cases of gender-based violence occurred.

Progress and difficulties

The military’s active participation in drawing up the final agreement to end the conflict could be seen as the greatest victory ever achieved by government forces. The FARC ceased to exist as an illegal armed organisation. The oldest guerrilla group on the continent had distanced itself from its dreams of taking power by armed force, choosing instead to negotiate an end to the armed conflict, rejoin Colombian society and participate in the country’s normal political processes.

The disappearance of the FARC as an armed group enabled government forces to attend to other destabilising factors threatening national security, such as the ELN guerrilla movement, major delinquent groups, and the types of criminality fostered by FARC dissidents who opposed the peace process.

The Armed Forces carried out an impeccable job in the design of the final agreement and have formed very important parts of its implementation. Incidents that were important enough to constitute a violation of the ceasefire were minimal compared to other experiences, with the outcome being that the ceasefire and laying down of arms by the FARC were completed in a timeframe that is unprecedented internationally.

Despite these successes, the FARC’s transition process has not been without difficulties. The government was very slow to prepare and provision the demilitarised zones, so the guerrillas lived for several months in unsuitable conditions. At the same time, as tends to be the case in other scenarios, the reinsertion process has been slow and inefficient (Herbolzheimer, 2018).

Furthermore, the climate of political polarisation in the country did not abate, despite the FARC’s decision to lay down its arms. The government’s information and education campaign failed to reduce the opposition and/or scepticism of a significant block of public opinion. Thus, a plebiscite rejected the initial version of the peace agreement, forcing a renegotiation in Havana in response to the principal concerns of its critics.

The Armed Forces are not untouched by the distrust felt by a major part of Colombian public opinion towards the peace process. Internal communications to keep military personnel informed about the steps involved in ending the conflict and the benefits that would result from the ending of hostilities could undoubtedly have been better designed. All of the above has provided fuel for successful disinformation campaigns run by sectors opposed to the peace process.

The National Police and Armed Forces participated actively in setting up measures to provide security for ex-combatants and their families, including setting up mixed arrangements for individual and group protection in the demilitarised territories. Despite these efforts, since the peace agreement was signed, 132 ex-combatants have been murdered, according to the director of the Special Unit of Investigations for the Colombian Attorney General’s Office (El País, 2019).

The key challenges facing Colombian government forces in building peace

In terms of implementing the agreements, even the FARC leaders themselves have stated that they have more trust in the efficiency of the Armed Forces and the National Police than in the state’s other civil institutions. In most of the regions that have been prioritised for stabilisation, the Armed Forces are the only institution with the credibility and capacity to remain on the ground and manage resources effectively.

A further challenge, not only for the Armed Forces, but for the Colombian state as a whole, is the capacity to strengthen the civil institutions involved in the implementation of the agreements so that their work is sustainable, transparent and effective. The weakness of institutions that have been compromised, particularly at the local level, has resulted in delays in implementing the next steps after the final agreement was achieved. But it has also sowed doubt among the former combatants (Kroc Institute, 2019) and, in some ways, has been a factor in the increasing number of ex-combatants distancing themselves from the reincorporation process: by February 2019 the estimated total was 2,300 dissidents, a large increase from about 300 at the time of the signing of the agreement, and part of the 13,000 who laid down their arms, according to statements by the commander of the Colombian Armed Forces (Reuters, 2019).

In a post-conflict scenario another of the challenges is to redefine the distribution of duties between the National Police and the Armed Forces. Ex-combatants need assurances of their safety, but responses to new threats to security are needed as well. The processes of stabilising territory and the post-conflict situation entail a transformation of the security and defence sector that requires a more comprehensive vision, with the active participation of all institutions and also – increasingly – of society.

Public money and international donations to implement the agreements must be safeguarded, as must their transparent implementation by an institutional matrix that is well coordinated and backed up by observers from the monitoring bodies.

And, finally, the drugs trade and corruption still constitute two huge obstacles to building peace in Colombia. Without finding a solution to what is seen as the fuel of the Colombian conflict, it will be hard to make progress in achieving a definitive peace. The increase in illegal crops, their profitability for drug-trafficking organisations, and the absence of a fresh approach on the part of the government and the international community to solving the problem, increase the difficulty of implementing the agreements and are even the cause of new conflicts. A peace process does not end with the signing of a peace agreement and the members of the guerrilla forces laying down their arms. Implementing the peace agreement must involve social, political and cultural transformations that prevent the proliferation of new cycles of violence.

Colombia’s Armed Forces have shown that they are not only able to perform on the battlefield, but also in the peace negotiations and the implementation of the peace agreements. Their commitment and professionalism in the implementation of the Havana agreement have become an example to the world. The challenges still remaining to consolidating peace in Colombia will need the participation of all of Colombia’s institutions and society, including the Armed Forces and National Police.

Technical Subcommittee for Ending the Conflict, Havana-Cuba, March 5, 2015.

Photo: Omar Nieto, OACP – Office of the High Commissioner for Peace

- This report solely and exclusively expresses the arguments and personal opinions of the authors, and in no way represents the official position of the Armed Forces, the National Defence Ministry or the Government of the Republic of Colombia.

- The FARC, a Communist guerrilla group with deep roots in the country areas; the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional/ELN), a movement inspired by the Cuban revolution and liberation theology that mobilised working class sectors and the left-wing intelligentsia; Maoist armed groups, like the Popular Liberation Army (Ejército Popular de Liberación/ EPL) and Revolutionary Workers’ Party (Partido Revolucionario de los Trabajadores/PRT); nationalists, like the 19th of April Movement (Movimiento 19 de abril/M-19), and the indigenous peoples’ Quintin Lame Armed Movement (Movimiento Armado Quintin Lame/MAQL). In 1993 the Socialist Renewal Splinter Group (Corriente de Renovación Socialista/CRS) broke away from the ELN. From the 1980s onwards several counter-revolutionary “self-defence” or “paramilitary” groups sprang up. These groups would merge into the United Self-Defence Units of Colombia (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia/AUC).

- Muela (2012), quoted in López-Meneses (2018).

- A Rand Corporation report entitled How Terrorist Groups End (Jones & Linicki, 2008) was particularly important in Colombia.

- In 2012 Jaramillo would become the High Commissioner for Peace and plenipotentiary for negotiating with the FARC in Havana.

- Norway and Cuba, the guarantor countries, supported this exercise by bringing in the experts

- Related material included definitions, objectives and timelines for the teams dealing with the Bilateral and Definitive Ceasefire and Cessation of Hostilities (BDCCH) and the Laying down of Arms; and rules governing the BDCCH; the M&VM; the deployment of units in the field and demilitarised zones; security; logistics; and the laying down of arms.

CIASE (Corporación de Investigación y Acción Social y Económica) and Corporación Humanas. 2017. Vivencias, aportes y reconocimiento: las mujeres en el proceso de paz en La Habana. https://www.humanas.org.co/alfa/dat_particular/ar/ar_95749_q_Las_mujeres_en_la_Habana_v2.pdf

El País. 2019. “¿Quiénes matan a los excombatientes?, lo que revelan investigaciones de la Fiscalía”. June 3rd. https://www.elpais.com.co/judicial/quienes-matan-a-los-excombatientes-lo-que-revelan-investigaciones-de-la-fiscalia.html

Herbolzheimer, K. 2016. Innovations in the Colombian Peace Process. NOREF Report. Oslo: NOREF.

Herbolzheimer, K. 2018. La implementación de la paz en Colombia: los retos de la reincorporación de las FARC. Informe Wilton Park/NOREF. https://www.wiltonpark.org.uk/event/wp1604

INDEPAZ (Instituto de Estudios para el Desarrollo y la Paz). 2013. Proceso de paz con las autodefensa unidas de Colombia. http://www.indepaz.org.co/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Proceso_de_paz_con_las_Autodefensas.pdf

Jones, S. & M. Linicki. 2008. How Terrorist Groups End. Santa Monica: Rand Corporation.

Kroc Institute (Kroc Institute for International Studies). 2019. Estado efectivo de implementación del acuerdo de paz de Colombia 2 años de implementación - Informe 3 Diciembre 2016 - Diciembre 2018. https://kroc.nd.edu/assets/321729/190523_informe_3_final_final.pdf

Lledín, J. & L. Carrillo. 2017. El cese bilateral: más allá del fuego. CINEP. https://www.cinep.org.co/publicaciones/es/producto/el-cese-bilateral-mas-alla-del-fuego

López-Meneses, C. E. 2018. “La injerencia extranjera en el conflicto colombiano” [Foreign interference in the Colombian conflict]. Revista Criterio Libre Jurídico, 15(1): 3-24.

M&VM (Monitoring and Verification Mechanism). 2017. Informe de cierre de las actividades del Mecanismo de Monitoreo y Verificación. September 22nd. https://unmc.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/informe_final_publico_221530r_sept_17_v_final_-_prensa_i.pdf

Nylander, D. & H. Salvesen. 2017. Towards an Inclusive Peace: Women and the Gender Approach in the Colombian Peace Process. NOREF Report. Oslo: NOREF.

Nylander, D. et al. 2018. Designing Peace: The Colombian Peace Process. NOREF Report. Oslo: NOREF.

OACP (Oficina del Alto Comisionado para la Paz). 2016. Acuerdo Final para la terminación del conflicto y la construcción de una paz estable y duradera. http://www.altocomisionadoparalapaz.gov.co/procesos-y-conversaciones/Documentos compartidos/24-11-2016NuevoAcuerdoFinal.pdf

OACP. 2018. Biblioteca del Proceso de Paz con las FARC-EP. Bogotá: Imprenta Nacional de Colombia.

Rangel, A. and L. Medina. 2008. ¿Qué, cómo y cuándo negociar con las Farc? Bogotá: Editorial Intermedio.

Reuters. 2019. “Exclusive: thousands of Colombian FARC rebels return to arms despite peace accord - military intelligence report”. June 4th. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-colombia-rebels-exclusive/exclusive-thousands-of-colombian-farc-rebels-return-to-arms-despite-peace-accord-military-intelligence-report-idUSKCN1T62LO

UNMC (United Nations Mission in Colombia). 2017. Informe de cierre de actividades del mecanismo de monitoreo y verificación. https://unmc.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/informe_final_publico_221530r_sept_17_v_final_-_prensa_i.pdf

UNVMC (United Nations Verification Mission in Colombia). 2018. “Remarks by Mr. Jean Arnault, Special Representative of the Secretary-General and Head of the United Nations Verification Mission in Colombia, on the situation in Colombia.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=al11odU91Y4

Velasquez, C. 2011a. Las fuerzas militares en la búsqueda de la paz con las Farc. Bogotá: Fundación Ideas para la Paz.

Velasquez, C. 2011b. La esquiva terminación del conflicto armado. Bogotá: La Carreta Editores.